Worth it #11 — Valuing Experimentation. Failure. And People Speaking Out.

Jeff Ikler here for Kirsten Richert with our weekly “Getting Unstuck” mini feature: Here in about five minutes, we extend the idea of this week’s podcast with some related content that we feel is definitely “Worth a Listen, Look or Read.”

The idea

This week we chatted with Dr. Randy Mahlerwein, the Assistant Superintendent over Secondary Schools in the Mesa Arizona Public Schools. One theme of Randy’s message was that educators need to create different types of learners with a different skill set from what we have typically produced in the past. Why? Because businesses are increasingly reliant on teams that work collaboratively to solve problems.

As innovation accelerates, we don't know what the workforce of the future is even going to look like. So we need to create more malleable, flexible, creative thinking, and critical thinking types of learners. And we hear a lot from industry that soft skills are lacking as well.

To accomplish that shift, Dr. Mahlerwein urges that schools empower their leaders and teachers to experiment with new approaches to instruction and learning, such as encouraging greater teacher and student agency, project-based learning, and expanded Career and Tech options. Experimental approaches need to be undertaken with a sense of urgency. “Failures” need to examined and supported as learning experiences.

Taking the idea deeper

And as with any major shift inside or outside education, staff could stand in the way in at least three ways:

People who have experienced a change-of-the-month club atmosphere at work are understandably skeptical and greet any new change with the expression “This too shall pass,” or “We tried ‘that’ before.”

There is a lack of trust that failure will really be tolerated, so it’s best not to try something new at all.

Changes are often driven top-down as opposed to excavating the wisdom of those in the trenches, so getting staff on board becomes a real challenge.

Note that these barriers all focus on human behavior and not on the technical aspects of change. Leaders need to address these human barriers if the change initiative is to succeed.

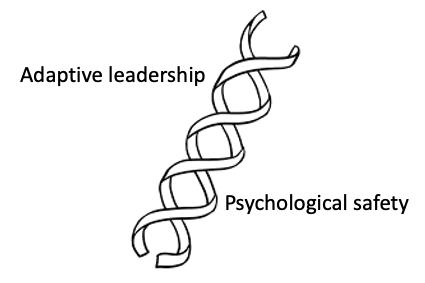

As Dr. Mahlerwein and I were talking, I realized that he epitomized two related ways to help overcome barriers. Think of these constructs as the strands of a DNA molecule..

Adaptive leadership

One strand, “adaptive leadership,” was popularized by Dr. Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linksky of the Kennedy School of Government and Harvard University. Basically “adaptive leadership” can be described as

“The art of leadership that helps others adjust to an unwelcome new reality.”

Their concept of “adaptive leadership” is fully explored in their book and in numerous articles, but if you want a simple and understandable entry point to the concept, read this one. Fundamentally, adaptive leadership recognizes that the world is changing rapidly, and organizations and individuals have to change with it. They have to adapt with it. Or else.

Five essential components define the adaptive leader:

They’re emotional intelligent. They know themself and others.

They’re transparent. They share information whenever possible.

They look to solve problems through a mindset of continuous change and continuous growth.

They’re open to feedback and have a willingness to change course if necessary.

They rely on internal and external partnerships to advance action.

Psychological safety

The second strand that I see Dr. Mahlerwein exercising is “psychological safety,” which Harvard University professor Dr. Amy Edmondson defines as

“The belief that the work environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking. People feel able to speak up when needed — with relevant ideas, questions, or concerns — without being shut down in a gratuitous way.

The most critical words in that definition are “speak up.” If organizations are to be truly healthy with staff knowledgeable of and contributing to the change, people have to feel they can speak their mind without fear of retribution.

Dr. Edmundson popularized this notion of organizational fearlessness and its positive repercussions in her book, The Fearless Organization. For a quicker entry point, check out her article, “How fearless organizations succeed.”

Leaders who believe in a culture of psychological safety, routinely do three things:

They clarify expectations and organizational purpose so that all staff have a filter by which to evaluate possible actions.

They practice a “learners mindset,” which blends humility and curiosity. They believe that it will be infinitely easier for staff to “speak up” if they see that the boss doesn’t have all the answers.

They express genuine appreciation for the thinking, speaking and actions of others. And they support failure as a learning tool.

Finally, Dr. Edmundson is quick to point out that practicing behaviors in an effort to reduce staff’s fear of speaking out doesn’t mean everyone has to agree, and it doesn’t guarantee high organizational performance. But leaders who routinely work to create the psychologically safe environment increase the likelihood that staff will feel part of something bigger than themselves and readily support changes that work toward achieving desired outcomes.

For additional insight into psychological safety, check out this TEDx Talk featuring Dr. Edmundson.

Putting the idea to work

Look again at the five behaviors of the adaptive leader. Which do you routinely exhibit? Which could you stand to develop a bit more?

Look again at the three behaviors leaders routinely exhibit to promote a psychologically safe environment. Think of your own leadership in change initiatives. Rate yourself on each behavior on a sale of 0 to 5 where “0” equals doesn’t exhibit and “5” means routinely exhibits. Hey, no one is looking at this but you. How much work do you have to do to create the psychologically safe environment?